103, 921 Stems: What We Grew in 2022

I’m curious how other folks keep records of what they harvest on the farm, so I thought I’d share mine. But first, why bother? There are so many reasons, but for me a lot of it is just that I like numbers, spreadsheets, and analyzing data. I love seeing trends pop out of a mess of numbers, and I enjoy learning the tools and programs that can help me do it. I know that’s not for everyone, so I won’t be offended if you dip out now.

“Even if you’re not a spreadsheet dork, keeping a brief record of what you harvest can at least help you predict what you’ll have in the future, both in terms of timeline and quantity.”

But even if you’re not a spreadsheet dork, keeping a brief record of what you harvest can at least help you predict what you’ll have in the future, both in terms of timeline and quantity. That can be super valuable when working with wholesale outlets or brides: you can let them know, “Well, we usually have lisianthus starting in early August, so I expect that we can (or can’t) supply them for your wedding, event, etc.” Using harvest records is how I was able to build my Flower Calendar that I use to help brides, florists, and curious folks.

Harvest Record-Keeping in the Field

We are a paper people. I use a harvest template, keep it on a clipboard, and use it throughout the week. It also serves as a way for me to show my staff what needs to be harvested and in what order, and I can put a “goal” or “limit” number of bunches on the sheet, too.

Here, you can see how we use hash marks to count our bunches, because there’s usually more than one of us harvesting the same thing at the same time. In the upper left corner of the “bunches” box I will put a goal number of bunches. Random note: It’s important to use pencil, because you can erase mistakes, and it won’t bleed and make a mess like pen.

Then I enter the data into a spreadsheet so I can see how much we’ve gotten for each week. While it would be nice to enter all the data directly into the spreadsheet with a phone or tablet, this just isn’t practical for us in the field. I hope to be entering our harvest data on the farm on a daily basis next year, though, instead of letting the sheets gather on a clipboard & taking them home to do over the course of a couple hours. Hopefully this will help me have a better running total of what I have in the cooler to sell.

The next thing we need to get better about, or be more consistent with, is identifying each planting and reporting harvests only from that planting. In the midst of a hurried harvest, this can feel like a drag, but at the end of the year when I’m trying to figure out how many bunches I got from each planting, it’s hard to do without complete data. But I still get some info from it. At the very least, I can predict which flowers we’ll have blooming when, and more or less how much, if I can remember how much we planted the year before. The ideal would be to have a figure for the average number of stems per plant for every species and variety — but I’m not hopeful I’ll ever get all of that. Perhaps for a few plants we’ll get close to that kind of knowledge and specificity.

“I know I purchased 2,450 ranunculus corms. I harvested 13,040 stems, for an average of 5.3 stems per corm.”

For some, it’s easier than others: I know I purchased 2,450 ranunculus corms. I harvested 13,040 stems, for an average of 5.3 stems per corm. I’m pretty pleased with that number, especially since some of them were butterfly ranunculus that can be less productive. My dahlia numbers are less encouraging: We dug up 1700 clumps, which would equate to the number of living plants we had (we didn’t leave any in the field this year), and my dahlia harvest numbers show 6900 stems harvested, for an average of just 4 stems per plant. That seems so low to me! I know I probably couldn’t have handled more dahlias coming in, but it makes me question my sense of how productive these plants are. In Specialty Cut Flowers by Allan Armitage and Judy Laushman, my flower growing bible, they say that “yields of 20 flowers per plant are not uncommon” (p. 235). Unless I’ve made a terrible error in my record keeping, my yields per plant are quite low.

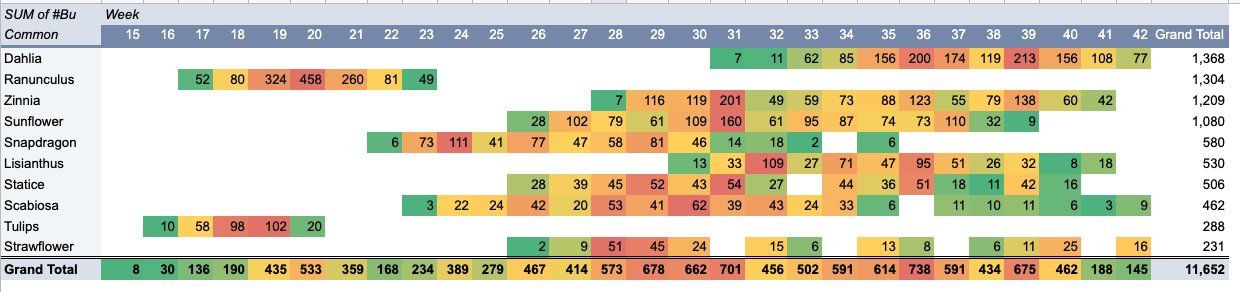

Anyhow, here’s a breakdown of what we harvested this year, and put some thought into the numbers that appear. I use pivot tables to help me summarize big swaths of data like I have from harvest record keeping. Below, see my harvest data, and then the pivot table summarizing the number of bunches per week. Pivot tables are a lot of fun, because you can cut and slice the data every which way, once you get the hang of it. After that, there’s a chart of bunches per week over the year.

What the raw data looks like after entering into the spreadsheet.

In the pivot table, I used conditional formatting on the top 10 producers, so I can easily see what their “hottest” weeks were. The bottom row shows my total bunches harvested per week, so you can see we got real hot in week 29—31, cooled off a bit and then ramped back up with dahlias etc in week 36.

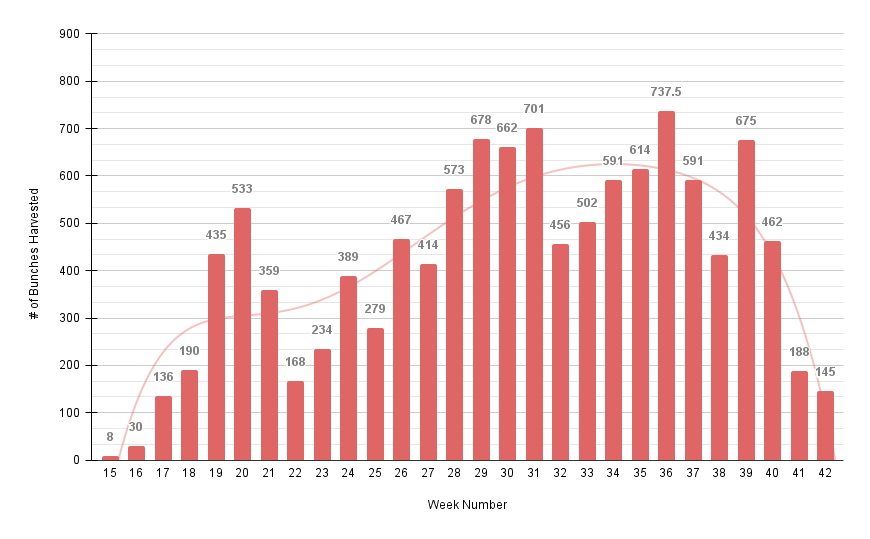

A column chart of our bunch production by week.

“ In all, we produced flowers for 27 weeks this year, from Week 15 to Week 42, and overall we cut 11,600 bunches, which works out to more than 103,000 stems. Our hands hurt.”

The chart is interesting because it shows the “unevenness” of the season: lots of stems from tulips and ranunculus in May, followed by that dependable and irritating June lull, then the summer flowers hit in July, and we gradually increase production with lisianthus and dahlias in August and September, followed by our post-frost crash. I’m hoping our peonies and other perennials will help even out the June slump. In all, we produced flowers for 27 weeks this year, from Week 15 to Week 42, and overall we cut 11,600 bunches, which works out to more than 103,000 stems. Our hands hurt. If our mums had not frosted and been kind of a general bummer, we’d have had flowers through November, for about 33 weeks. Next year, I’ll be careful with the mums, and we’ll hopefully have a better narcissus year, along with our forced bulbs that should be blooming in March and April. I’m also hoping we can do some winter snapdragons in our awesome greenhouse. So perhaps a 40-week season is on the horizon!

With this kind of broad data, it’s important to know what question you’re asking, and to make sure that the analysis you’re using can accurately answer that question without giving you misleading information. There are so many questions to ask, and so many ways of looking at the data. After finding the answer to your question, ask another one that can help you make decisions for the future. Questions you could ask:

What was our highest producer? What is the most productive flower per bed-foot?

What was our lowest producer? Should we cut that crop or give it better conditions or more space?

When are we producing the most flowers? How can we fill gaps in production?

For a quickie, I’ll just list our ‘top 10’ producers by bunches —note that bunches may be of different sizes. Dahlias are a 5-stem bunch, but lisianthus are 10, and oregano or sea oats can be a 20-30 stem bunch. Summarizing by bunch means I can estimate potential income from wholesale; just multiply bunches by your price, and there’s your potential income. Of course, selling every single bunch wholesale may not be possible, but one can dream. If we had sold every bunch of just my top 10 sellers at wholesale prices, we would have grossed well over $100k, minus the Colorado Flower Collective’s commission on those sales. We definitely didn’t do that, haha, but those flowers did go to other outlets like weddings, subscriptions, and market.

Anyway, on to the Top Ten:

Dahlias: 1,368 bunches (5 stems)

Ranunculus: 1,304 bunches

Zinnia: 1,209 bunches

Sunflower: 1,080 bunches (5 stems)

Snapdragon: 580 bunches

Lisianthus: 530 bunches

Statice: 506 bunches

Scabiosa: 462 bunches

Tulips: 288 bunches

Strawflower: 231 bunches

Not a lot of surprises here, except the strawflower, which really wasn’t doing well, but I guess we still got a good yield. I’d love to see it up there with zinnias though. The snapdragons, too — I’ve had seasons of 10,000 stems, so twice what we got this year, but we had a hard time with fungus gnats and didn’t get our third and fourth successions in the ground.

While we’re at it, how about a Bottom Ten?

I recorded less than 10 bunches cut of each of these. Here’s why and some thoughts.

Solidago — First year perennial, and we definitely cut more that I didn’t record. Keeping it.

Everlasting — There were plenty of flowers, but I didn’t have the energy to cut their fiddly stems. Not sure if I’m keeping this or not.

Feverfew — So sad, our plants didn’t overwinter and our plugs in the greenhouse were all eaten by fungus gnats.

Bluebell — We could have had more but I just didn’t cut it. It’s a small patch in the far corner of the farm. And, it’s more of a purple than a true blue, so not a very in-demand color.

Euphorbia — I think these were volunteer plants that I harvested randomly one day for a specific customer.

Cup & Saucer Vine — You know, I’ve never gotten a lot of blooms from these, and stems are usually quite short. They can be a striking addition to a compote centerpiece or a very short-term wearable arrangement, but they also require a trellis, and I’m no longer sure they’re worth the space and time.

Ammobium — This one was in a crappy spot in the field, and I think it’s adorable and unique, which is what our florists (including me!) want. So we’ll keep trying.

Meadow Rue — This one was a huge success at the Collective! Again, it’s unique and gorgeous, but it was my first year growing it, so I used the year to observe it more than to cut it. But I’d love to grow more of it, and it wasn’t terribly hard to start from seed.

Allium — Poor allium. I just had one hundred bulbs of A. caeruleum in the ground, and they seemed unhappy for some reason. So not a lot of blooms, and I let most of them go to seed. In the midst of ranunculus harvest it can be tough to make time for “piddly” things. I’d love to have a huge field of ‘Purple Sensation’ or ‘Mount Everest’, but they are expensive bulbs.

Leucojum — Sad about this one too! Leucojum is an excellent cut, but like most of my daffodil-type bulbs, this one was super short and unhappy this spring with all the hot weather and dry winds.

Well, I hope this was interesting and perhaps helpful. What are your record-keeping procedures, and how do you analyze your harvest data?